No one said a word. Listening to the whirl of helicopter blades above, we sat in our open safari vehicle and watched as a white rhino — known as C21 — lumbered out of the bush and onto a dirt road. She turned as if to increase the distance between us, then suddenly fell to the ground after being hit with an anesthetic from the helicopter above.

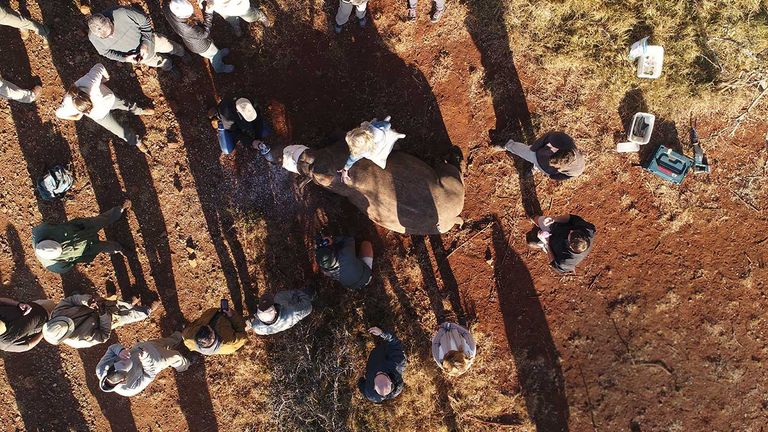

A medical team of more than a dozen swarmed almost instantaneously. Once given the OK, the group of guests (including myself) from South Africa’s Thanda Safari Private Game Reserve quickly followed to witness a dehorning procedure.

A helicopter shoots an anesthetic dart from above.

A helicopter shoots an anesthetic dart from above.

Credit: 2020 Christian Sperka Photography

Some got close enough to touch the sleeping giant. Others watched from afar. As the exam began, veterinarians discovered C21’s horn was badly cracked; the process would be a bit more complicated than usual.

Along with being a symbol of status and wealth, rhino horns are in high demand on the black market for their use in traditional Chinese medicine. Several years ago, the safari reserve — along with other privately owned reserves in the South African province of KwaZulu-Natal — began dehorning their rhinos to dissuade the poaching that threatens their survival. (The reserve also boasts an extensive anti-poaching team.)

Four rhinos were poached at Thanda in 2016. In December of the same year, the reserve made the decision to begin dehorning. Since the change in policy, Thanda hasn’t lost a single animal.

“Maybe 10 years ago, a reserve like us was probably spending about $3,000 to $4,000 per month on anti-poaching measures,” said Truman Ndlovu, reserve operations and security manager for Thanda. “Currently, it’s $17,000 to $34,000.”

Standing steps from C21’s head, I unexpectedly became an active participant when asked by a staff member if I could help measure the rhino’s horns. I didn’t hesitate, dropping my knees to the dirt and grabbing the tape measure. The swift movement brought me face to face with the creature in a way I never imagined; even with the blindfold over her eyes, her facial expressions were powerful. When she let out a sigh, I found myself whispering to her that all would be OK. It was eerily reminiscent of consoling an injured puppy, or even a young child.

The dehorning procedure uses a battery-powered saw to horizontally cut the horn above the growth plate. There are no nerves in the horn, which is made of keratin (the same substance found in human hair and fingernails). Like trimming a fingernail, there’s no pain, and a rhino’s horn grows back, typically within a couple years.

Dehorning is a painless process, and the horns grow back.

Dehorning is a painless process, and the horns grow back.

Credit: 2020 Christian Sperka PhotographyWhen the procedure was complete, C21’s horn was taken to an undisclosed, secure location, and my group headed back to our safari vehicle. Within minutes, the 2-year-old rhino was up on her feet, heading back into the cover of the African bush. It was almost as if nothing had happened.

“It doesn’t affect their behavior, and it doesn’t affect their ability to protect themselves,” said Bradley Viljoen, a veterinarian at the nearby Mtubatuba Veterinary Clinic. “At the end of the day, it’s just increasing their chance of survival.”

After the procedure, rhinos are released back into the wild.

After the procedure, rhinos are released back into the wild.

Credit: 2020 Christian Sperka PhotographyThe $1,821 fee to participate in this excursion covers the expense of the helicopter, the pilot and two veterinarians — Thanda doesn’t make a profit. The price is divided by the number of guests taking part, so if a client expresses interest, the property will query others staying on-site to lower costs and increase access. Taking part in a rhino dehorning is a moving experience, particularly for those searching for activities with purpose.

In addition to the dehorning and twice-daily game drives, my days at Thanda were filled with guided bush walks, elephant and cheetah tracking and a visit to a traditional Zulu homestead. Accommodations include a private villa, nine bush suites at Thanda Safari Lodge, 15 luxury safari tents and A-frame style chalets for guests volunteering with the on-site Ulwazi Thanda Research Program.

The Details

Thanda Safari Private Game Reserve

www.thandasafari.co.za